- Home

- en

- datalogger-monitoring-systems

- nuuk

- applications

- diagnostic_errors

In 2019, the European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (EFLM) Preanalytical Phase Working Group (WG-PRE) developed a specific checklist - called PREDICT - to avoid preanalytical diagnostic errors in clinical trials.

This checklist focuses in particular on the most important pre-analytical aspects of blood sample management in clinical trials:

- Test selection

- Patient preparation

- Sample collection

- Management and storage

- Sample transportation

- Pre-test sample collection

Laboratory errors

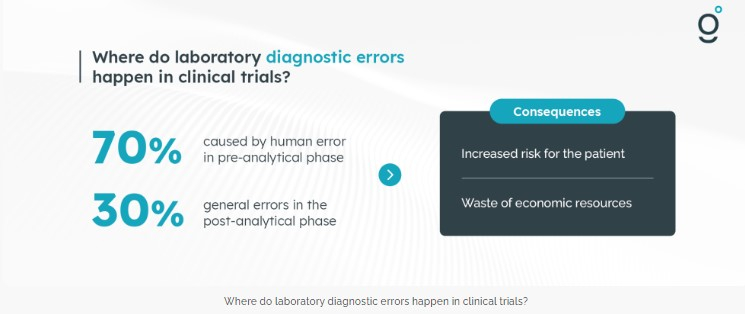

Errors happen, even in laboratory diagnostics. Although many efforts have been made to improve standardization and harmonization of various activities throughout the testing process, in vitro diagnostics is a relatively safe environment compared to other diagnostic disciplines. Most of these errors (approximately 60-70%) are due to manual activities in the pre-analytical phase, followed by post-analytical errors (approximately 20-30%) and analytical errors. The various consequences of these potential errors include increased patient risk and waste of economic resources as well as organizational problems inside and outside the laboratory. Pre-analytical quality is an essential requirement of clinical trials because there is a tangible risk that some clinical trials will not deliver the actual results due to a variety of laboratory errors, including those that occur in the pre-analytical phase.

Laboratory tests in clinical trials

Laboratory diagnostics play an essential role in clinical trials, as many diagnostic tests are used to determine whether or not a trial participant meets the eligibility criteria; they are also used to assess baseline values of many parameters, which may then be modified by the clinical intervention, as well as to demonstrate the efficacy of investigational products and to monitor the safety of trial participants throughout the clinical trial.

The adoption of stringent pre-analytical requirements is as mandatory for clinical diagnostic tests as it is for clinical trials, as the risk of errors in the latter scenario can result in several unfavorable consequences (e.g. rejection of samples due to non-compliance in the pre-analytical phase could subsequently lead to the exclusion of not only the specific samples, but also the entire data of the person concerned).

Failures in clinical trials

There is consolidated evidence that the risk of a misleading clinical trial result (i.e. a positive or negative result) is higher than the risk of a false positive result. i.e. a positive or negative result) is particularly high - i.e. an event that falls under the traditional concept of "lost in translation from the bench to the bedside", which encompasses the failure to translate basic research findings into effective clinical interventions.

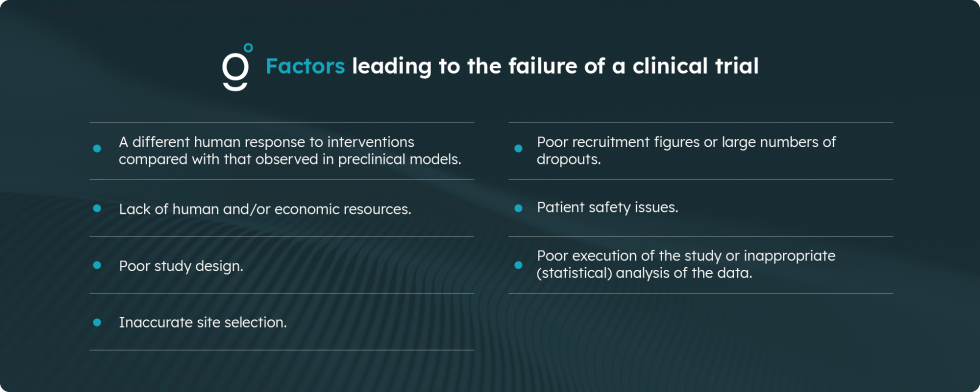

There are many factors that lead to the failure of a clinical trial (apart from lack of efficacy or safety concerns about the intervention), including:

- Different human response to the interventions compared to that observed in preclinical models

- Lack of human and/or economic resources

- Poor study design

- Inaccurate site selection

- Poor recruitment numbers or a high number of dropouts

- Problems with patient safety

- Poor study conduct or inadequate (statistical) analysis of data

Among these various factors, diagnostic errors (including pre-analytical errors) are usually overlooked as a potential cause of clinical trial failure, although there is growing evidence to suggest the opposite.

A recent report published by Schultze and Irizarry identified the main sources of uncertainty in laboratory data obtained during safety assessment studies:

- Unfamiliarity with standard operating procedures (SOPs)

- Misidentification of samples

- Equipment malfunction

- Failure of quality control

- Test failures

It is worth noting, that the risk of clinical trial failure due to delayed processing of blood samples for glucose testing has also been highlighted. Indeed, blood tubes that cannot be centrifuged for up to 24 hours after vein collection will experience a gradual (false) drop in glucose concentration, which may ultimately affect the interpretation of data used to assess the health status of potential study participants. In multi-center studies, the use of different types of blood collection tubes or additives can be a source of divergent results, which greatly affects statistical interpretation.

In addition, the use of inappropriate pre-analytical procedures or failure to follow standard operating procedures for the collection, processing and storage of biospecimens has been shown to introduce a negative bias in trial results and can also affect the reproducibility of scientific data.

It is critical to have a standardized recording and documentation system for all pre-analytical conditions during the process of patient preparation, biospecimen collection and storage to rule out pre-analytical bias in future studies. In particular, the cumulative risk of preanalytical bias gradually increases with the complexity of the study, being lower for single-centre studies, intermediate for multicentre studies characterized by multiple peripheral sampling sites and local testing, and predictably highest for multicentre studies involving many peripheral sampling sites and a single reference laboratory (i.e. centralized testing). In the latter case, not only do local procedures for blood sample collection and handling need to be standardized, but strict harmonization of local administration and sample transport to reference laboratories is also required.

Management of preanalytical variability in clinical trials

There are no guidelines for the management of preanalytical variability in clinical trials, and there is no specific guidance for standardizing or harmonizing the different preanalytical steps within a clinical trial, be it single or multicentre. For all these reasons, the PREDICT checklist was developed.

Choosing the most appropriate laboratory tests

Choosing the most appropriate laboratory tests is as important in routine clinical practice as it is in clinical trials. In the latter, it often happens that study protocols are revised and contain outdated, redundant or even useless tests because old habits persist in the preparation of the protocols - together with insufficient or insufficiently updated knowledge about the importance of the tests. The use of the most appropriate and up-to-date laboratory tests in clinical trials - due to their potential usefulness for determining the eligibility of participants, for detecting adverse events and for defining clinical outcomes - is as mandatory here as in routine clinical practice.

The method of analysis should also be selected according to the objective of the test, i.e. it should be determined in advance whether the test is to be used for screening, diagnosis, prognosis, therapeutic monitoring or follow-up. In this way, the analysis, analytical technique and test concentration limits can be selected according to the diagnostic performance and adapted to the intended use of the study protocol.

Patient preparation

It is important that patient preparation for sample collection is standardized. This includes the exact standardization of blood collection from one patient to another when samples are collected at a single center, but a standardized procedure is also essential when blood is collected at different centers. This requires accurate recording of clinical data, followed by strict standardization of fasting time, collection time, abstinence from cigarette smoking and coffee drinking, and a rest period prior to blood collection; the patient must also be in a standardized position during collection.

Collection and handling of blood samples

The study protocol contains clear information on sample type and volume, sample matrix, blood collection device and blood collection tubes/additives as well as the time of tourniquet application, preferred venipuncture site, order of collection and mixing of samples. The use of identical automated tube labelling devices is a viable option to improve standardization.

Preparation, transport and/or storage of blood samples

The risk of analytical bias is lower with centralized testing, but local analysis would limit the risk of pre-analytical bias due to sample transport. Both solutions are suitable as long as a detailed protocol with precisely standardized analytical or pre-analytical procedures is provided. In clinical trials where samples are shipped from distant collection centers to the reference laboratory, it is essential to centrifuge the samples on site if there is a concrete risk that the stability of the analytes in the serum or plasma is compromised during transport. Regardless of whether centrifugation is performed on-site or in the reference laboratory, centrifugation conditions must be standardized and the serum or plasma must be separated as soon as possible after centrifugation.

Sample transport conditions (i.e. time and temperature) must be accurately standardized, recorded and monitored. For samples that cannot be analyzed immediately, they must be stored at different temperatures and storage times according to the available knowledge about the stability of the analytes. Repeated freezing and thawing cycles should usually be avoided, preferably by aliquoting the samples in volumes corresponding to the analytical need before storage according to the study protocol.

Tools such as the platform developed by Groenlandia Tech guarantee traceability in such logistics processes. A key element of the platform is the Nuuk cool box: a device with a real-time control system that optimizes the logistics process, improves the safety of the contents and reduces laboratory costs.

Nuuk guarantees various aspects, such as real-time control of the internal temperature, an integrated alarm system - which informs of any possible impact or damage in the transport process -, full access control where only the original user and the recipient can access the contents, and a cooling technology that can be adapted to different temperature ranges.

Pre-test sample collection

Finally, in clinical trials where biobanks are used for long-term storage of biological material, pre-test sample collection can be an additional critical point. It is recommended that standard operating procedures be made available to all participating laboratories to standardize the procedures for preparing samples for testing; they should also include procedures for thawing and mixing samples and clear guidance that inappropriate samples should not be analyzed. This is particularly important for hemolyzed samples, which are the number one cause of test suppression in clinical laboratories.

- +

Sources

1. Lippi G, Guidi GC, Plebani M. One hundred years of laboratory testing and patient safety. Clin Chem Lab Med 2007;45:797-8.10.1515/CCLM.2007.176Search in Google ScholarPubMed

2. Lippi G, Plebani M. A Six-Sigma approach for comparing diagnostic errors in healthcare-where does laboratory medicine stand? Ann Transl Med 2018;6:180.10.21037/atm.2018.04.02Search in Google ScholarPubMed PubMed Central

3. Lippi G, Betsou F, Cadamuro J, Cornes M, Fleischhacker M, Fruekilde P, et al. Preanalytical challenges - time for solutions. Clin Chem Lab Med 2019;57:974-81.10.1515/cclm-2018-1334Search in Google ScholarPubMed

4. Padoan A, Sciacovelli L, Zhou R, Plebani M. Extra-analytical sources of uncertainty: which ones really matter? Clin Chem Lab Med 2019;57:1488-93.10.1515/cclm-2019-0197Search in Google ScholarPubMed

5. Plebani M, Aita A, Padoan A, Sciacovelli L. Decision support and patient safety. Clin Lab Med 2019;39:231-44.10.1016/j.cll.2019.01.003Search in Google ScholarPubMed

6. Schiff GD, Hasan O, Kim S, Abrams R, Cosby K, Lambert BL, et al. Diagnostic error in medicine: analysis of 583 physician-reported errors. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1881-7.10.1001/archinternmed.2009.333Search in Google ScholarPubMed

7. Lippi G, Bonelli P, Cervellin G. Prevalence and cost of hemolyzed samples in a large urban emergency department. Int J Lab Hematol 2014;36:e24-6.10.1111/ijlh.12135Search in Google ScholarPubMed

8. Cadamuro J, Fiedler GM, Mrazek C, Felder TK, Oberkofler H, Kipman U, et al. In-vitro hemolysis and its financial impact using different blood collection systems. J Lab Med 2016;40:49-55.10.1515/labmed-2015-0078Search in Google Scholar

9. Simundic AM, Lippi G. Preanalytical phase - a continuous challenge for laboratory professionals. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2012;22:145-9.10.11613/BM.2012.017Search in Google Scholar

10. Lippi G, von Meyer A, Cadamuro J, Simundic AM. Blood sample quality. Diagnosis (Berl) 2019;6:25-31.10.1515/dx-2018-0018Search in Google ScholarPubMed

11. Banfi G, Lippi G. The impact of preanalytical variability in clinical trials: are we underestimating the issue? Ann Transl Med 2016;4:59.10.21037/atm.2016.04.10Search in Google ScholarPubMed PubMed Central

12. Lippi G. The irreplaceable value of laboratory diagnostics: four recent tests that have revolutionized clinical practice. EJIFCC 2019;30:7-13.Search in Google Scholar

13. Badrick T. Evidence-based laboratory medicine. Clin Biochem Rev 2013;34:43-6.Search in Google Scholar

14. Lippi G, Simundic AM, Rodriguez-Manas L, Bossuyt P, Banfi G. Standardizing in vitro diagnostics tasks in clinical trials: a call for action. Ann Transl Med 2016;4:181.10.21037/atm.2016.04.10Search in Google Scholar

15. Simon R. Lost in translation: problems and pitfalls in translating laboratory observations to clinical utility. Eur J Cancer 2008;44:2707-13.10.1016/j.ejca.2008.09.009Search in Google ScholarPubMed PubMed Central

16. Hwang TJ, Carpenter D, Lauffenburger JC, Wang B, Franklin JM, Kesselheim AS. Failure of investigational drugs in late-stage clinical development and publication of trial results. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1826-33.10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6008Search in Google ScholarPubMed

17. Morgan B, Hejdenberg J, Hinrichs-Krapels S, Armstrong D. Do feasibility studies contribute to, or avoid, waste in research? PLoS One 2018;13:e0195951.10.1371/journal.pone.0195951Search in Google ScholarPubMed PubMed Central

18. Wong CH, Siah KW, Lo AW. Estimation of clinical trial success rates and related parameters. Biostatistics 2019;20:273-86.10.1093/biostatistics/kxx069Search in Google ScholarPubMed PubMed Central

19. Cummings JL, Morstorf T, Zhong K. Alzheimer's disease drug-development pipeline: few candidates, frequent failures. Alzheimers Res Ther 2014;6:37.10.1186/alzrt269Search in Google ScholarPubMed PubMed Central

20. Ioannidis JP, Bossuyt PM. Waste, leaks, and failures in the biomarker pipeline. Clin Chem 2017;63:963-72.10.1373/clinchem.2016.254649Search in Google ScholarPubMed

21. Fogel DB. Factors associated with clinical trials that fail and opportunities for improving the likelihood of success: a review. Contemp Clin Trials Commun 2018;11:156-64.10.1016/j.conctc.2018.08.001Search in Google ScholarPubMed PubMed Central

22. Crucitti T, Fransen K, Maharaj R, Tenywa T, Massinga Loembé M, Murugavel KG, et al. Obtaining valid laboratory data in clinical trials conducted in resource diverse settings: lessons learned from a microbicide phase III clinical trial. PLoS One 2010;5:e13592.10.1371/journal.pone.0013592Search in Google ScholarPubMed PubMed Central

23. Lippi G, Simundic AM. The preanalytical phase in the era of high-throughput genetic testing. What the future holds. Diagnosis (Berl) 2019;6:73-4.10.1515/dx-2018-0022Search in Google ScholarPubMed

24. Schultze AE, Irizarry AR. Recognizing and reducing analytical errors and sources of variation in clinical pathology data in safety assessment studies. Toxicol Pathol 2017;45:281-7.10.1177/0192623316672945Search in Google ScholarPubMed

25. Lippi G, Nybo M, Cadamuro J, Guimaraes JT, van Dongen-Lases E, Simundic AM. Blood glucose determination: effect of tube additives. Adv Clin Chem 2018;84:101-23.10.1016/bs.acc.2017.12.003Search in Google ScholarPubMed

26. Betsou F. Biospecimen processing method validation. Biopreserv Biobank 2015;13:69.10.1089/bio.2015.1321Search in Google ScholarPubMed

27. Ellervik C, Vaught J. Preanalytical variables affecting the integrity of human biospecimens in biobanking. Clin Chem 2015;61:914-34.10.1373/clinchem.2014.228783Search in Google ScholarPubMed

28. Gaignaux A, Ashton G, Coppola D, De Souza Y, De Wilde A, Eliason J, et al. A biospecimen proficiency testing program for biobank accreditation: four years of experience. Biopreserv Biobank 2016;14:429-39.10.1089/bio.2015.0108Search in Google ScholarPubMed PubMed Central

29. Stellino C, Hamot G, Bellora C, Trouet J, Betsou F. Preanalytical robustness of blood collection tubes with RNA stabilizers. Clin Chem Lab Med 2019;57:1522-9.10.1515/cclm-2019-0170Search in Google ScholarPubMed

30. Lehmann S, Guadagni F, Moore H, Ashton G, Barnes M, Benson E, et al. Standard preanalytical coding for biospecimens: review and implementation of the sample preanalytical code (SPREC). Biopreserv Biobank 2012;10:366-74.10.1089/bio.2012.0012Search in Google ScholarPubMed PubMed Central

31. Robb JA, Gulley ML, Fitzgibbons PL, Kennedy MF, Cosentino LM, Washington K, et al. A call to standardize preanalytic data elements for biospecimens. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2014;138:526-37.10.5858/arpa.2013-0250-CPSearch in Google ScholarPubMed PubMed Central

32. Robb JA, Bry L, Sluss PM, Wagar EA, Kennedy MF, College of American Pathologists Diagnostic Information, et al. A call to standardize preanalytic data elements for biospecimens, part ii. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2015;139:1125-8.10.5858/arpa.2014-0572-CPSearch in Google ScholarPubMed

33. International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Standard 20387:2018: biotechnology - biobanking - general requirements for biobanking. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Standardization, 2018.Search in Google Scholar

34. Moore HM, Kelly A, Jewell SD, McShane LM, Clark DP, Greenspan R, et al. Biospecimen reporting for improved study quality. Biopreserv Biobank 2011;9:57-70.10.1089/bio.2010.0036Search in Google ScholarPubMed PubMed Central

35. Vaught J, Abayomi A, Peakman T, Watson P, Matzke L, Moore H. Critical issues in international biobanking. Clin Chem 2014;60:1368-74.10.1373/clinchem.2014.224469Search in Google ScholarPubMed

36. Kellogg MD, Ellervik C, Morrow D, Hsing A, Stein E, Sethi AA. Preanalytical considerations in the design of clinical trials and epidemiological studies. Clin Chem 2015;61:797-803.10.1373/clinchem.2014.226118Search in Google ScholarPubMed

37. National Institutes of Health. Guidelines for good clinical laboratory practice standards. Bethesda, MD, USA: National Institutes of Health, 2019.Search in Google Scholar

38. World Health Organization. Good Clinical Laboratory Practice (GCLP). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2009.Search in Google Scholar

39. Ezzelle J, Rodriguez-Chavez IR, Darden JM, Stirewalt M, Kunwar N, Hitchcock R, et al. Guidelines on good clinical laboratory practice: bridging operations between research and clinical research laboratories. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2008;46:18-29.10.1016/j.jpba.2007.10.010Search in Google ScholarPubMed PubMed Central

40. Tuck MK, Chan DW, Chia D, Godwin AK, Grizzle WE, Krueger KE, et al. Standard operating procedures for serum and plasma collection: early detection research network consensus statement standard operating procedure integration working group. J Proteome Res 2009;8:113-7.10.1021/pr800545qSearch in Google ScholarPubMed PubMed Central

41. Guest PC, Rahmoune H. Blood bio-sampling procedures for multiplex biomarkers studies. Methods Mol Biol 2017;1546:161-8.10.1007/978-1-4939-6730-8_12Search in Google ScholarPubMed

42. Lippi G, Plebani M, Guidi GC. The paradox in translational medicine. Clin Chem 2007;53:1553.10.1373/clinchem.2007.087288Search in Google ScholarPubMed

43. Lippi G, Bovo C, Ciaccio M. Inappropriateness in laboratory medicine: an elephant in the room? Ann Transl Med 2017;5:82.10.21037/atm.2017.02.04Search in Google ScholarPubMed PubMed Central

44. Cadamuro J, Ibarz M, Cornes M, Nybo M, Haschke-Becher E, von Meyer A, et al. Managing inappropriate utilization of laboratory resources. Diagnosis (Berl) 2019;6:5-13.10.1515/dx-2018-0029Search in Google ScholarPubMed

45. Kiechle FL, Arcenas RC, Rogers LC. Establishing benchmarks and metrics for disruptive technologies, inappropriate and obsolete tests in the clinical laboratory. Clin Chim Acta 2014;427:131-6.10.1016/j.cca.2013.05.024Search in Google ScholarPubMed PubMed Central

46. Kaul KL, Sabatini LM, Tsongalis GJ, Caliendo AM, Olsen RJ, Ashwood ER, et al. The case for laboratory developed procedures: quality and positive impact on patient care. Acad Pathol 2017;4:2374289517708309.10.1177/2374289517708309Search in Google ScholarPubMed PubMed Central

47. Morse JE, Calvert SB, Jurkowski C, Tassinari M, Sewell CA, Myers ER. Evidence-based pregnancy testing in clinical trials: recommendations from a multi-stakeholder development process. PLoS One 2018;13:e0202474.10.1371/journal.pone.0202474Search in Google ScholarPubMed PubMed Central

48. Montagnana M, Trenti T, Aloe R, Cervellin G, Lippi G. Human chorionic gonadotropin in pregnancy diagnostics. Clin Chim Acta 2011;412:1515-20.10.1016/j.cca.2011.05.025Search in Google ScholarPubMed

49. Lippi G, Sanchis-Gomar F. "Ultra-sensitive" cardiac troponins: requirements for effective implementation in clinical practice. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2018;28:030501.10.11613/BM.2018.030501Search in Google ScholarPubMed PubMed Central

50. Association for Clinical Biochemistry and Laboratory Medicine. A statement from the ACB and LIMS manufacturers regarding CKD-EPI issued 09th February 2016. http://www.acb.org.uk/docs/default-source/documents/ckd-epi-statement-feb-2016-.pdf?sfvrsn=2. Last accessed, October 20, 2019.Search in Google Scholar

51. Lippi G, Mattiuzzi C. The biomarker paradigm: between diagnostic efficiency and clinical efficacy. Pol Arch Med Wewn 2015;125:282-8.10.20452/pamw.2788Search in Google ScholarPubMed

52. Simundic AM, Bölenius K, Cadamuro J, Church S, Cornes MP, van Dongen-Lases EC, et al. Joint EFLM-COLABIOCLI Recommendation for venous blood sampling. Clin Chem Lab Med 2018;56:2015-38.10.1515/cclm-2018-0602Search in Google ScholarPubMed

53. Lippi G, Simundic AM. The EFLM strategy for harmonization of the preanalytical phase. Clin Chem Lab Med 2018;56:1660-6.10.1515/cclm-2017-0277Search in Google ScholarPubMed

54. Simundic AM, Cornes M, Grankvist K, Lippi G, Nybo M. Standardization of collection requirements for fasting samples: for the Working Group on Preanalytical Phase (WG-PA) of the European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (EFLM). Clin Chim Acta 2014;432:33-7.10.1016/j.cca.2013.11.008Search in Google ScholarPubMed

55. Kong FS, Zhao L, Wang L, Chen Y, Hu J, Fu X, et al. Ensuring sample quality for blood biomarker studies in clinical trials: a multicenter international study for plasma and serum sample preparation. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2017;6:625-34.10.21037/tlcr.2017.09.13Search in Google ScholarPubMed PubMed Central

56. Cureau FV, Bloch KV, Henz A, Schaan CW, Klein CH, Oliveira CL, et al. Challenges for conducting blood collection and biochemical analysis in a large multicenter school-based study with adolescents: lessons from ERICA in Brazil. Cad Saude Publica 2017;33:e00122816.10.1590/0102-311x00122816Search in Google ScholarPubMed

57. Casson PR, Krawetz SA, Diamond MP, Zhang H, Legro RS, Schlaff WD, et al. Proactively establishing a biologic specimens repository for large clinical trials: an idea whose time has come. Syst Biol Reprod Med 2011;57:217-21.10.3109/19396368.2011.604818Search in Google ScholarPubMed PubMed Central

58. Marton MJ, Weiner R. Practical guidance for implementing predictive biomarkers into early phase clinical studies. Biomed Res Int 2013;2013:891391.10.1155/2013/891391Search in Google ScholarPubMed PubMed Central

59. Favaloro EJ, Oliver S, Mohammed S, Ahuja M, Grzechnik E, Azimulla S, et al. Potential misdiagnosis of von Willebrand disease and haemophilia caused by ineffective mixing of thawed plasma. Haemophilia 2017;23:e436-43.10.1111/hae.13305Search in Google ScholarPubMed

60. Lippi G, Cadamuro J, von Meyer A, Simundic AM. Practical recommendations for managing hemolyzed samples in clinical chemistry testing. Clin Chem Lab Med 2018;56:718-27.10.1515/cclm-2017-1104Search in Google ScholarPubMed

61. Simundic AM, Baird G, Cadamuro J, Costelloe SJ, Lippi G. Managing hemolyzed samples in clinical laboratories. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2019:1-21. doi: 10.1080/10408363.2019.1664391. [Epub ahead of print].10.1080/10408363.2019.1664391Search in Google ScholarPubMed

62. Lippi G, Salvagno GL, Mattiuzzi C. Public perception of diagnostic and laboratory errors among Internet users. Diagnosis (Berl) 2019;6:385-6.10.1515/dx-2018-0103Search in Google ScholarPubMed

Navigation

Produkte

Branchen & Anwendungen